Archives for Interpreting - Page 2

The interpreter’s there in the interview room at the dead of night, with the suspect and the interviewing police officer. What’s the interpreter’s role in ensuring best evidence?

In child protection cases the interpreter’s Code of Practice advocates impartiality and objectivity. Coming at it from a different perspective, social services professionals often feel that their interpreter colleagues should get more involved. So when the interpreter is caught in the middle as the mouthpiece of a vulnerable child how does he win that young person’s trust so that he feels comfortable enough to tell his story without the unintended consequence of potentially undermining best evidence?

A services provider working with the elderly wants you as the interpreter to take the lead in building a rapport with an elderly gent whose needs they must understand, but who won’t talk to his social worker. Our Code of Practice is clear that it’s outside the role and professional competence of the interpreter to add mediation and negotiation to the task they’re there to perform: interpreting. How do you support your social services client to communicate with their client, but without yourself becoming an active third party in the exchange?

These were some of the issues Dr Rebecca Tipton, Lecturer in Translation and Interpreting Studies at The University of Manchester, explored with us and our packed audience of interpreters and translators at our AGM last week.

Dr Tipton’s research centres on the challenges of public service interpreting and we’d invited her to speak at our AGM as part of our continuous professional development programme. As you’ll have gathered from the professional dilemmas she outlined, interpreters daily face what can be heart-rending situations involving some of the most vulnerable people in our society. Highly qualified in languages and interpreting, our interpreters working with front line services not infrequently find themselves called upon to go way beyond their role, asked to support other professionals in their – very different – areas of expertise. For example, one of our interpreters was recently left alone by a social worker who assumed she would take over her role, settling a frightened young mum and victim of domestic abuse into her room in a refuge.

Dr Tipton’s talk at our AGM is just one of the ways we help our interpreters work out the best course of action in cases like this. Between now and January we’re running a series of CPD workshops exploring a whole range of dilemmas – all based on real life challenges our interpreters have faced. We also run courses for service providers, helping them manage translation and interpreting services as effectively and professionally as possible.

If you’d like more information on our CPD programme and our training for service providers, contact my colleague Dominique van den Berg at training@cintra.org.uk

I’m Jerry Froggett, Chief Executive here at Cintra Translation.

I’m Jerry Froggett, Chief Executive here at Cintra Translation.

High quality. Highly professional.

That’s my team!

To talk to us, call +44 (0)1223 346870

Image credit: Child reaching / free images.com/Aron Kremer

Hi, I’m Serap and I am DPSI LAW qualified Turkish interpreter. I live in the UK and work regularly for Cintra, interpreting and translating Turkish to English and vice versa. I like and enjoy my job – let me give you an idea of a typical day in my working life.

Hi, I’m Serap and I am DPSI LAW qualified Turkish interpreter. I live in the UK and work regularly for Cintra, interpreting and translating Turkish to English and vice versa. I like and enjoy my job – let me give you an idea of a typical day in my working life.

My busiest working day is usually a Sunday, and this weekend was no exception. I’m a qualified police interpreter and also work for healthcare trusts, so although we were going out for Sunday lunch with family, I’m always prepared to go to a police station or hospital at short notice. We take two cars, so my husband doesn’t get stranded. And I keep an overnight bag in the boot. Once, after interpreting for the police over four days and nights, a court usher asked me why I wasn’t wearing a suit. Now I take clothes for interpreting in any situation – police stations, courts, hospital waiting rooms and wards, people’s homes and sadly, even mortuaries.

This Sunday the call from Cintra – a police job – came while we were still at home, so it was easy to for us to go into the routine that gets me on my way as quickly as possible. Cintra works with forces across the East of England and the Midlands, so while my husband made me coffee and a sandwich for the journey, I found the police station on my sat nav. My average ‘commute’ time is 2.5 hours, and I keep in touch with Cintra by Bluetooth, so if I’m delayed the Cintra manager will let the client know. That lets me focus on the job, and I like it that Cintra know all their interpreters by name. To some agencies interpreters are just a number – and I’m not so keen on that!

Once I get to the police station I find out if I’m interpreting for a suspect, a witness or perhaps the victim of a crime. The work is highly confidential, so, sorry, I won’t be telling any true crime stories about this weekend’s particular case! The commonest are drink driving and sexual assault, but I have interpreted in a double murder investigation, and that was quite chilling, believe me.

It’s the interpreter’s job to translate everything the Turkish and English speakers say when we’re in an interview room. Even if a suspect or witness says in Turkish: ‘Don’t translate this.’ Or if the police officers talk about the weather, I translate the chit chat: everyone needs to know what’s going on, just as if the interview was all in English.

And I have to translate exactly what is said. Sometimes, because of the different ways our languages work, or even because of the educational level of the speaker, the words we translate sometimes don’t make much sense to the hearer. For example, Turkish has no pronouns equivalent to he and she: we just use it. So a suspect or a witness might tell me in Turkish: ‘It was talking to me and then it ran up and punched me.’

If I was translating this into English in a social situation, I could make assumptions about the two different people the speaker is referring to. But in a police interview, the interpreter can’t make assumptions. I have to say: ‘He or she was talking to me and another he or she punched me.’ When the police officers look at me like I’m crazy, I suggest they ask me to ask the Turkish speaker to explain for themselves in more detail.

We got through this weekend’s interview quite quickly, and although I missed Sunday lunch, I did get home in time to put my daughter to bed and check with the child minder for after school tomorrow. I’ve been booked to interpret for a health visitor who’s weighing a two-week-old baby. I saw the mum when she was pregnant, so it will be nice to see the new-born – and find out if it’s a he or a she: I’m pretty certain this one won’t be an it!

To work with us here at Cintra, all interpreters and translators must be trained and qualified as Serap is to the required professional standards. Our linguists are assessed and security-vetted as part of the registration process, and are required to follow our Code of Conduct which stresses confidentiality and impartiality.

To work with us here at Cintra, all interpreters and translators must be trained and qualified as Serap is to the required professional standards. Our linguists are assessed and security-vetted as part of the registration process, and are required to follow our Code of Conduct which stresses confidentiality and impartiality.

Cintra is one of the few agencies with its own in-house interpreter training and Diploma in Public Services in Interpreting exam centre. Through our specially devised courses, foreign language speakers who are new to interpreting can be trained and assessed and start working, before obtaining further qualifications, including the Diploma in Public Service Interpreting.

Let’s imagine we’ve had a busy morning and are on our way to grab a cup of coffee together. With us is a colleague who speaks three European languages, including English, but is a native Russian speaker.

Let’s imagine we’ve had a busy morning and are on our way to grab a cup of coffee together. With us is a colleague who speaks three European languages, including English, but is a native Russian speaker.

We’re doing what you do in narrow corridor: walking fast, talking, gesticulating and twisting around. Just in time, I spot a pool of liquid up ahead.

In a split second, and ever mindful that 28% of the 77,593 non-fatal workplace injuries reported in 2013/14 were slips and trips, I throw a warning over my shoulder to you and our Russian-speaking colleague.

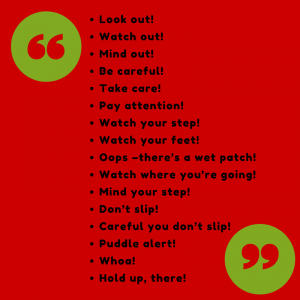

OK, you’ve been there. You can picture the scene. Now, let’s run the soundtrack. But hold on a minute – which of the 17* ways of saying, ‘Careful, someone’s spilt their coffee, don’t slip!’ will I plump for?

One of the great strengths and delights of English is the sheer number of words in the language: every time I open my mouth or put pen to paper I’ve got a working vocabulary of around 35,000 words to choose from. And I’ll keep adding one new word a day until I’m well into middle age.

Non-native speakers living in the UK work hard to keep up. They add between two and three new English words to their working vocabulary every day. But, by any count, building up a good store of health and safety speak is going to take them some time.

Non-native speakers aren’t only up against it coming to grips with our mix of idiom, dialect and regional accent. We love our catchphrases culled from sport, pop, TV and film. And don’t forget to factor in trending slang, and even perhaps the odd workplace obscenity. It’s no wonder that making assumptions about the language we use to warn of danger is fraught with danger.

English is rich and can be very precise, but for the non-native speaker working in the UK, our colourful, colloquial, idiomatic language is often more like a trippy, slippery minefield of misunderstanding – in other words, it’s an accident just waiting to happen.

*You can probably think of even more.

We’re working with an increasing number of companies to translate their Health and Safety policies and procedures into the languages their workers speak and read fluently. Companies and HR managers employing us to translate everything from policy documents to induction packages and factsheets report strong business reasons for investing in quality translation services. We can also provide interpreters in over 100 languages so that you can communicate with staff and customers who speak languages other than English.

related post: Penalties, prevention and ISO 45001: three reasons to translate health and safety policies for your migrant workforce

Follow Cintra Translation and Interpreting Services on Facebook

I spent 22 hours in police custody last week. So did my wife.

I spent 22 hours in police custody last week. So did my wife.

Don’t worry, we’re both qualified police interpreters, so it’s quite normal for the police to invite us down to the station for a few words. We don’t normally work together, but they needed both of us for this job; seven people held in custody on suspicion of false imprisonment. Though we knew what the term on the charge sheet meant, we did some research and found the legal definition of false imprisonment. We translated it and discussed it. We had all evening to prepare in our mother tongue for the sorts of issues and legal terms we’d need to translate quickly and accurately the next day.Watch movie online The Transporter Refueled (2015)

We got to the police station at 9am. The sergeant said: ‘I hope you’re ready to spend the next 12 hours with us, it’s going to be a long one’. He was more than right. Police interpreters are used to working anti-social hours and long hours don’t scare me. It’s a good way to challenge your brain.

We’d known that it was never going to be a straightforward job, and unusually, we’d even had time to prepare. Then, just as I was interpreting the ‘rights’ for the first suspect, he was further arrested for rape. My job just got even more challenging. More circuits in my brain lit up. I remembered back to the Diploma of Police Interpreting course I took with Cintra. We had a lovely lady trainer – a police retired officer – who shared with us some of her experiences getting to know the victims of sex crimes – and the criminal perpetrators. She introduced us to words that didn’t need definitions.

Back to the sergeant: he asked me to help interpret for the doctor so he could take intimate samples from the alleged male offenders. Well, the interpreter’s job is to explain what’s going on, and the sergeant was happy I was a male.

The solicitors started arriving, so things got rolling. Each consultation was one and a half hours long. Then solicitors had to be changed as they discovered conflicts. Before I realised, six hours had gone past. Back in the waiting room on a short break, I could hear my stomach rumbling, but it wasn’t the right time for lunch. A couple of new solicitors arrived. We had to get things going. You can eat later, I told myself.

Two hours later another interpreter arrived. That was my lucky break – I snuck out for a juicy McDonalds. And I managed to get some chicken for my wife. It was hard to find each other between interviews and consultations. She didn’t really enjoy that meal, bless her.

Half an hour’s break and that BigMac recharged my batteries. Back at the interviews the detectives were meticulous. They were all ears as I interpreted their blunt questions and the suspect’s answers. All this while my wife and the other interpreters were in adjacent interview rooms. Like me, they were listening intently and choosing their words carefully. It went on and on, and then it was time for the very last interview.

You could say I was the last man standing, so lucky me, I got to interpret for the last interview. It was 1 o’clock in the morning when we entered the interview room. The solicitor had to put a lot of questions. One and a half hours later: conflict! With that last solicitor gone, the police had run out of legals to call on.

After two hours of phone calls, looking in vain for solicitors, the police officers finally reached a solution. They could get a legal representative at another police station, so we bundled into cars and managed a quick transfer. Well, even at 3 o’clock in the morning, it was a 50-minute drive. Good thing it took me closer to home. And now my wife had finished her shift, at least she was able to turn up the expensive ‘central heating’ and sleep in the car.

I realised I was at that stage, past sleep, where I could go on and on. Just as well, because this final interview was very long and the questions from the detectives seemed like they would peel the skin off this man they had arrested on suspicion of rape.

Finally finished at 7am. I was not so much relieved as frustrated when I left the police station – 22 hours after walking in.

That’s it. That’s the end of my story. I can’t tell you why it was frustrating, or give you more details. I’m a police interpreter and the work I do is highly confidential.

Our interpreter blogger, Cristian, is originally from Romania and is a qualified interpreter with a Diploma in Police Interpreting.

Photo credit: Geoffrey Lebrec/freeimages.com

A great article in yesterday’s Times from Jenni Russell, talking about social norms now that we live in a world where we need to work with and understand people from so many different cultures.

A great article in yesterday’s Times from Jenni Russell, talking about social norms now that we live in a world where we need to work with and understand people from so many different cultures.

She says that the Foreign Office is launching the Diplomatic Academy, essentially a finishing school for diplomats, to help them through these social and cultural minefields and make them the best in the world.

Of course, it’s not just diplomats who need this sort of knowledge – it’s everyone in business who wants to export their products to other countries or has a multicultural workforce. As Jenni puts it:

‘How many of us know that Finnish acquaintances should never be hugged or kissed; that two or three-minute pauses in conversation are common and should not be interrupted, and that a careless British phrase such as “We should have lunch” will be taken as a solemn invitation when all we mean is: “I like you but I may well never see you again”?

‘Or that the Dutch get down to frank business negotiations immediately and will proceed fast once consensus is reached, whereas the Portuguese expect several discursive meetings before any clear results? That the French would prefer you to blow your nose in private, that Americans expect brief questions and answers in social situations and get uncomfortable if anyone holds the floor for a long time; that you should not show anger or attempt to tell jokes in Singapore? That Turks will be deeply offended if the sole of your shoe faces them? Or that in some Asian cultures, by advancing on anybody with your arm outstretched, insisting on eye contact and saying: “Hello, I’m Bill”, (or Jane), you might be offending on three fronts at once?’

Our Go Global product includes notes on culture for each language you want your documents translated into – and of course, we can translate documents and provide interpreting for your workforce too.

You can read the full article here (paywall)

http://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/opinion/columnists/article4351487.ece

Tess Wright Chief Executive

image credit: Henkster www.free.images.com

I was thinking about this over the weekend, when I listened to Any Questions on BBC Radio 4 (guaranteed to get my blood boiling for all sorts of reasons!)

I was thinking about this over the weekend, when I listened to Any Questions on BBC Radio 4 (guaranteed to get my blood boiling for all sorts of reasons!)

The last question was about whether it is necessary or desirable for the Welsh government to spend time and significant amounts of money on translating information into Welsh, providing interpreters and teaching Welsh in schools, when it is spoken by only a small proportion of people living in Wales.

The questioner was booed when he asked the question, and the panel unanimously (perhaps running scared) said that it was both necessary and desirable (although a substantial part of the audience later disagreed when they voted on it).

I had a look for some information on this, and found an article on the BBC website –http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-11304255  It’s from 2010, but still interesting reading.

It’s from 2010, but still interesting reading.

The Foundation for Endangered Languages held a conference in Camarthen, West Wales, appropriately enough to discuss the facts that although there are over 6000 languages spoken worldwide, up to 1000 of these are only spoken by a handful of people – and 25 languages are lost every year.

Samuel Johnson said ‘language is the dress of thought’ – if you lose the language, you lose the knowledge it expresses, and also individualism and identity.

Others say this is nonsense – it’s about cultural change, how do we ever progress if we have a romantic desire to cling on to the past, to things that were once useful but are now irrelevant. We should focus on teaching people useful languages like Chinese Mandarin, Spanish and English.

I can’t make up my mind on this. Part of me loves the idea that we don’t just do things because of their usefulness, and I think the past matters – not just romantically, but because of what we can learn from it. The other part thinks that when resources are limited and need is great, we should spend money where it will do most good – and if the language hadn’t progressed, we would still be speaking Anglo Saxon, or Middle English – which were surely of their time and not relevant for now (much as I love Chaucer!)

What do you think? Do add your comments below.

Tess Wright, Chief Executive

image credit: Pontus Edenberg / www.edenberg.com

I was listening to Midweek on Radio 4 last week and was fascinated by a guy called Benny Lewis, who says he couldn’t speak any foreign languages when he left school but now speaks ten, including Mandarin, Arabic, Portuguese and Hungarian!

I was listening to Midweek on Radio 4 last week and was fascinated by a guy called Benny Lewis, who says he couldn’t speak any foreign languages when he left school but now speaks ten, including Mandarin, Arabic, Portuguese and Hungarian!

I don’t think he means he can speak them well enough to do interpreting or translation, but enough to hold a conversation with the people in whichever country he is in that goes beyond ‘please’, ‘thank you’ and ‘where are the toilets?’

Enough to give him an impression of the language and culture – by joining in – that is much richer than the superficial impression most visitors would receive if they can’t understand the language.

He does it by total immersion – going to live in whichever country whose language he wants to learn and refusing to speak English. One of his main techniques seems to be don’t make excuses such as ‘it’s too hard’ or ‘I’m too old’ or ‘they’ll think I’m an idiot’ – these rang a bell with me!

He’s just been made National Geographic’s Traveler of the Year on the back of all his learning trips.

You can hear the programme via the Radio 4 website – http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b03y13zd

and you can visit the website of the man himself at http://www.fluentin3months.com/about/

So what do you think – is it possible to learn a language well enough in three months to do more than get by as a visitor? And is it just the British who are scared of looking stupid when they try and speak other languages?

Look forward to your comments below.

Tess Wright, Chief Executive